The following post details the Nowhere Men’s journey from February 13 – 19:

Story Highlights:

- The mines of Potosi take us to a dark place

- We play with the light of the salt flats of Uyuni

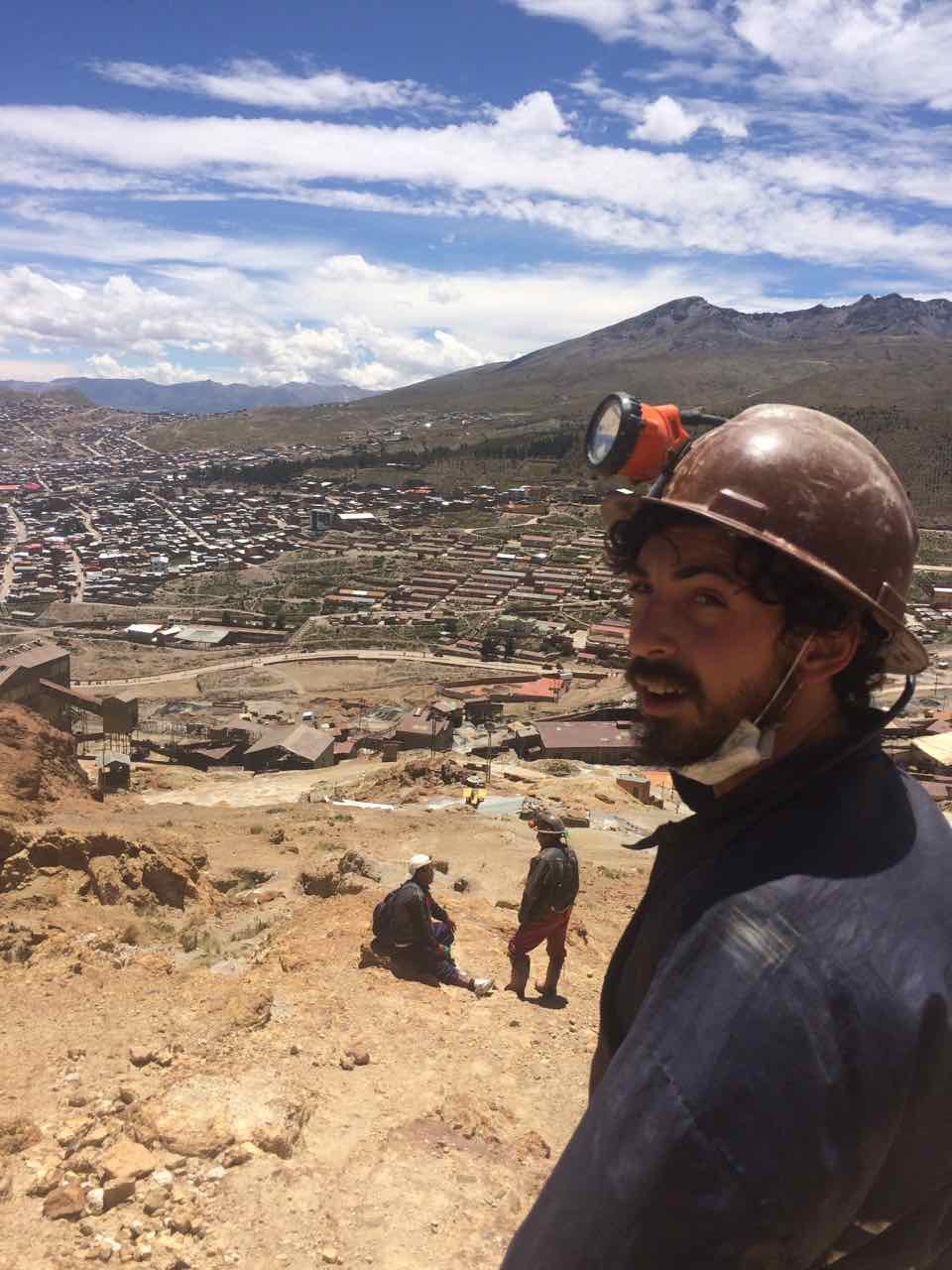

Conflicted. That’s putting lightly how we thought about taking a tour of an active silver mine in Potosi, Bolivia. On the one hand, we had an obligation to document life as honestly and authentically as we could, everywhere we go. And to that end, the mines in Potosi are the cornerstone of the small city in the heart of Bolivia. The town was founded on the discovery of valuable minerals in the depths of the hills surrounding this highland valley. It has served as the driving force of life here ever since. In that vein, we felt it would be a disservice to the people who embrace their rugged lifestyles in the mines if we were to visit this town and make no mention of its soul.

On the flip side, a tour would be the very definition of poverty tourism. A fleeting and brief investigation of this industry and those who keep its engines running borders on exploitation. Could we balance these conflicting perspectives on what we were about to do?

The first step was to find an agency. Big Deal Tours advertises themselves as the only agency in town owned and operated by miners themselves. This seemed to us a major victory in our search for the absolution of guilt that haunted our task to tour these mines, like a dark and long shadow at the cusp of sunset.

It turned out to be more than a wise decision. We met Pedro, the man who would serve as our guide for the day. He was funny and jovial, in spite of his frequently rehearsed lines about the tour and about us as tourists. He boasted a brief biography that we admired with a solemn nod of solidarity.

Pedro began working in the mines at the innocent age of 10. He spent 9 solid years toiling in the dark depths of the mines before shifting careers to guiding tours. He picked up English somewhere along the way without the aid of any formal education. Now he proudly advertises his agency’s reputation as the guys in town he really know what life is like in the mines.

After a stopover at the miner’s market where we picked up goodie bags for the men at work (coca leaves, dynamite and juice), we did a quick mini tour of the refinery, where the silver and zinc undergoes some sort of chemical processing so that it is ready to export abroad.

We anticipated a real sense of pity. We expected to confirm our preconceived perception that the miners themselves, at the nasty bottom of the totem poll of the mining industry, would be responsible for lifting up the profiteering businessmen on their shoulders. We thought their anger would be directed at the disproportional allocation of the spoils of this business, that foreign companies were poaching off of the resources in Bolivia and the workers who toil to extract it from the depths of the Earth. It would be a marked example of the ugly face of globalization. We were wrong.

Pedro had grievances, but it wasn’t directed where we expected. Rather, he projected a world where miner’s get what they earn and can even accumulate serious wealth in the claustrophobic confines of the mine’s coffers. He painted a brotherly portrait of the lives of the men who descend into the mines. Everybody is in it together and looks out for one another. Life is tough, but not without its pleasures and rewards. A hot soup at the end of a long day. A pint of 96% corn-based booze to wash away a week’s work.

We learned that, as far as Pedro and his compatriots were concerned, the real enemy is the politician. Men like President Evo, who we had read stands up for the disenfranchised indigenous contingency of the country. In reality, Pedro insisted, Evo is a lot of talk and little substance. He promised Potosi a legitimate and serviceable hospital, a place that would treat the endless ailments of the miners, who suffer all kinds of lung diseases and bodily injuries from the nature of the job. Instead, Evo’s grandiose promises amounted to nothing. Instead, when his uncle got sick from the mine’s suffocating chokehold, he had to spend buckets of money to gain treatment in the nearby city of Sucre.

That Pedro started working in the mine when he was just 10 years old is illegal, but he claims not uncommon. The nonexistent oversight by the government facilitates such practices. But as far as the miners are concerned, they have no problem breaking these soft regulations and doing what it takes to get by in life. If the government won’t help them, then they’ll help themselves.

Regardless of the pride one takes from life in the mines, Pedro admitted that he wants an easier path for his own son. He’s already learning English, he brags, and is well on his way. And although 9 years in the mines was enough for him, his buddies don’t all feel the same way. We’d imagined a job as a tour guide would be something that others would be jealous of, but in reality it’s not that way.

“I encourage my friends to try out leading tours. Many of them try it out and then in the end, decide the days are too long and the pay not good enough. They prefer working in the mines.”

We’ve seen the good, the bad, and the ugly during this exhaustive survey across quarters of Latin America. We’d thought this episode in Potosi’s mine would fit like a glove into the “ugly” quadrant. As it turns out, the truth here departed with our preconceived notion. Characteristics of all facets of humanity existed. The daily toil of a day fishing for precious minerals from the sea of rocks in the walls of the earth is ugly when one considers it in a vacuum. But like all of us, both good and bad comes from what these men think of as just their way of making a living. The work day ends, they enjoy some rest, a hot meal and maybe they even dip a bit into the buck they made that day to indulge in life’s simple pleasures. As outside observers, all we could do was show some respect and let this exploration sink in as we drove out of town and on to our next, brighter adventure.

….

We picked up a local farmer as we neared Uyuni. He nearly ran from the side of the road at the sight of our car to catch a ride. We happily picked him and he enthusiastically jumped at our offer of some coca leaves. A weathered Indian man dressed in modern clothes, a full head of salt and pepper hair and oblong glasses, Señor García told us about his quinoa farm as he ripped up coca leaves one at a time with his one strong hand. He left the leaves to pick at in a pile on his old school style fedora. When he walked out of the car at the town’s outskirts we found a place to park and wandered around the center. Just another short term traveler we happily could share a lift with.

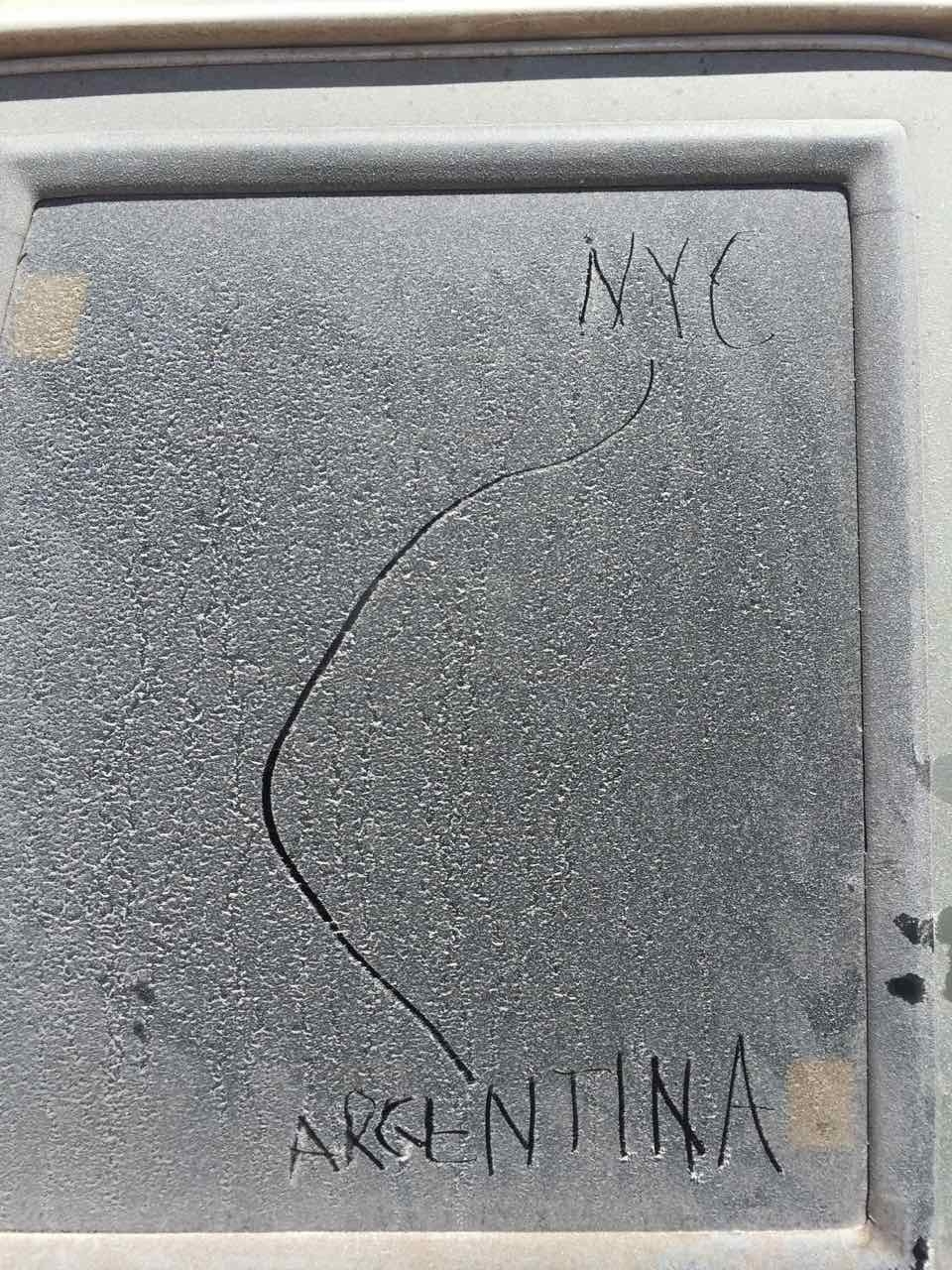

Tours leave Uyuni for the nearby salt flats at designated times throughout the day. We were able to coerce one such agency to simply let us follow them out. We were sure we could find it on our own, as its 400 square miles and hard to miss when you look anywhere in a westerly direction. Still, treacherous holes perilous to the untrained eye could lead us and our lovely Velita into ill-fated dangers.

We buddied up to the driver of the car, Elvis, who we knew would like us more as the day wore on and so would our shenanigans.

The flats glistened in the foreseeable distance. 23 kilometers stood in between us and this one-of-a-kind geological phenomenon. We cruised on well-paved highway until we hit Colchani, a small gateway town at the entrance to the flats. After some washboard roads, we bounced onto a flatter surface. It was, unmistakably, the beginning of miles and miles of glasslike land.

Music blasted out of our speakers and we matched its intensity with our own pulsating excitement. Eric waved the camera in all directions so as not to miss any angle, and then back at the driver and passenger still in the car. Then we took things to another level. Eric climbed out of the front seat and stood on the windowsill, filming above, below, and across Velita. Brian soon joined, leaping out of the back window and letting the salt dried air fly into his face and hair. Not to miss out, Alex joined the action, one hand on the wheel, the other lifting his torso out of the car and in front of the windshield. The ride out to the middle of the flats generated a euphoria around us we couldn’t control.

And then, the caravan stopped. The tour trucks brimming with camera-toting tourists from Japan and Korea found a place to settle in about 4-inch deep water. Here in the rainy season, luck’s timing granted us an even more astounding natural reaction: the shallow pond that sat atop the salt flat’s basin beget a mirror-like illumination from land to sky. The fluffy clouds swimming in the sea of blue sky above bounced back onto the Earth’s surface, reproducing its image in an angelic fashion.

We danced and rejoiced with wonder. Into our red ninja suits we dressed, contrasting the splendor of our surroundings with the outrageous bright blare of the outfits. Our ninja suits summarized our own emotions; we were in awe and blooming joy like a brilliant rose in an early spring’s day.

Our mission before us was clear from there: take a series of hilarious perspective photos that stand as a hallmark of any tourist who journeys to this endless expanse of dried whiteness. We put our creative hats on and got to work. The results speak for themselves.

The group of tourists couldn’t help but crack with laughter at our red-tinted photo tirade. They asked to take photos with us and we happily obliged. The next several hours ticked on like this, exchanging photos and laughter.

As the sun tracked its daily course across the sky, the view it brought us in this specific corner of the Earth was anything but regular. The sky’s ordinary darkening hew, mixed with swirls of orange and yellow, rebounded off of the ocean of salt and generated geometrical symmetries of shadows upon anything and everything in sight. Our eyes interpreted the world before as a Van Gogh painting come to life.

We knew this couldn’t be the end. We hadn’t had our fill. So, as dusk’s grip deepened, we committed ourselves to another day’s visit.

It rained all night and a threatening silver sky sat still above Uyuni well into midday. Nonetheless, we risked tossing Velita back into the fray. She would have to withstand a second day of the poisonous salt parade. We promised we’d get her a long and thorough wash when it was all said and done.

We followed the midday tour procession to the abandoned train cemetery and goofed off with some spooky ghost sequences amidst the hoards of excitable tourists. Before returning to Salar, we tried a trick to save a few bucks at the gas pump. Bolivia notoriously charges a doubling fee to extranjeros (foreigners) in need of gasoline, so we crept in the vicinity of a gas station and asked a Bolivian to help us out a bit. We’d give him our 30-liter Gerry can and a small tip if he’d use his national ID to get us the Bolivian price. Happy to earn a quick buck, this modest family man kindly accepted our deal. Soon enough, we had all the gas we needed and raced out to the Salt Flats to follow the tours to the salty seas. We leveraged this trick again multiple times in the coming days. Every cent saved counts.

We had to squint to see at all. The brightness was blinding. The sky, no different that on any other day, suddenly adopted a sort of toylike aura. Like we were in an animated cartoon, the brightness of the world around us made us feel more like we were in a video game than any real life location. If Mongolia is where land and sky meet, then the salt flats of Uyuni are where land and sky melt together.

On this day we’d have to take extra care. The previous night’s onslaught of rain had inundated the dried up salt desert with a knee deep layer of water. Taking supreme care, we risked Velita’s long term health yet again and skidded across the tundra until we’d arrived at a safer zone.

We made base camp and went to work. Using the 10-second timer on Brian’s camera, we snapped all the wittiest shots we could think of. Our little red selves in a jar peanut butter; our tiny red bodies holding up the world; insect-size versions of us fighting over a giant Thunderbird bar. The potential was limitless. And so was our sense of splendor.

The months wear on and our time on the road sometimes weighs on us like soggy clothes from getting caught in a rainstorm. It’s hard to keep up the enthusiasm, the creativity and the fun. Disillusionment and a “been there done that” dreariness is real. It’s also something that is antithetical to our entire philosophy.

A market, a teleferico, a waterfall, a marvelous view of the mountains. These are all things that 10 months ago sent us into a tailspin of the excitement. Now it’s just another market, another view, another hike. This is the next psychological battle we face; it is the next frontier for our travel-tested minds. The solution? Keep it fresh.

It takes a real jolt to get us back on track and we’ve realized, that’s okay. It’s okay to skip that colonial town. It won’t be that different from the last one, at least from where we’re standing. We won’t worry about checking out that old church or those amazing ruins. Instead, we b-lined it for the salt flats. We’ve learned to cut out the fat and bite right into the tender meat that is a place unlike any other.

Hey you! Thanks for reading.

Want to join our weekly mailing list for more great updates from us?