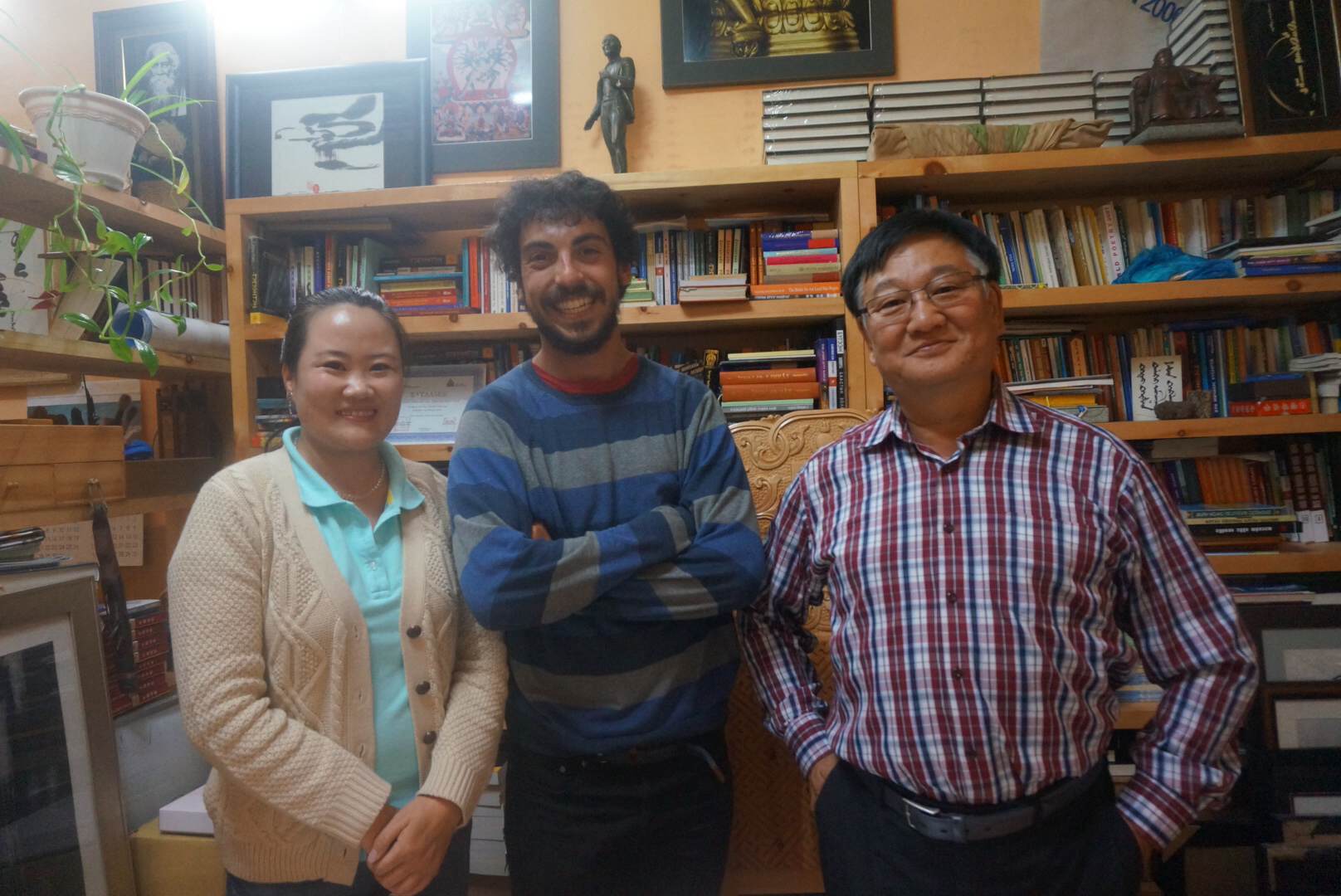

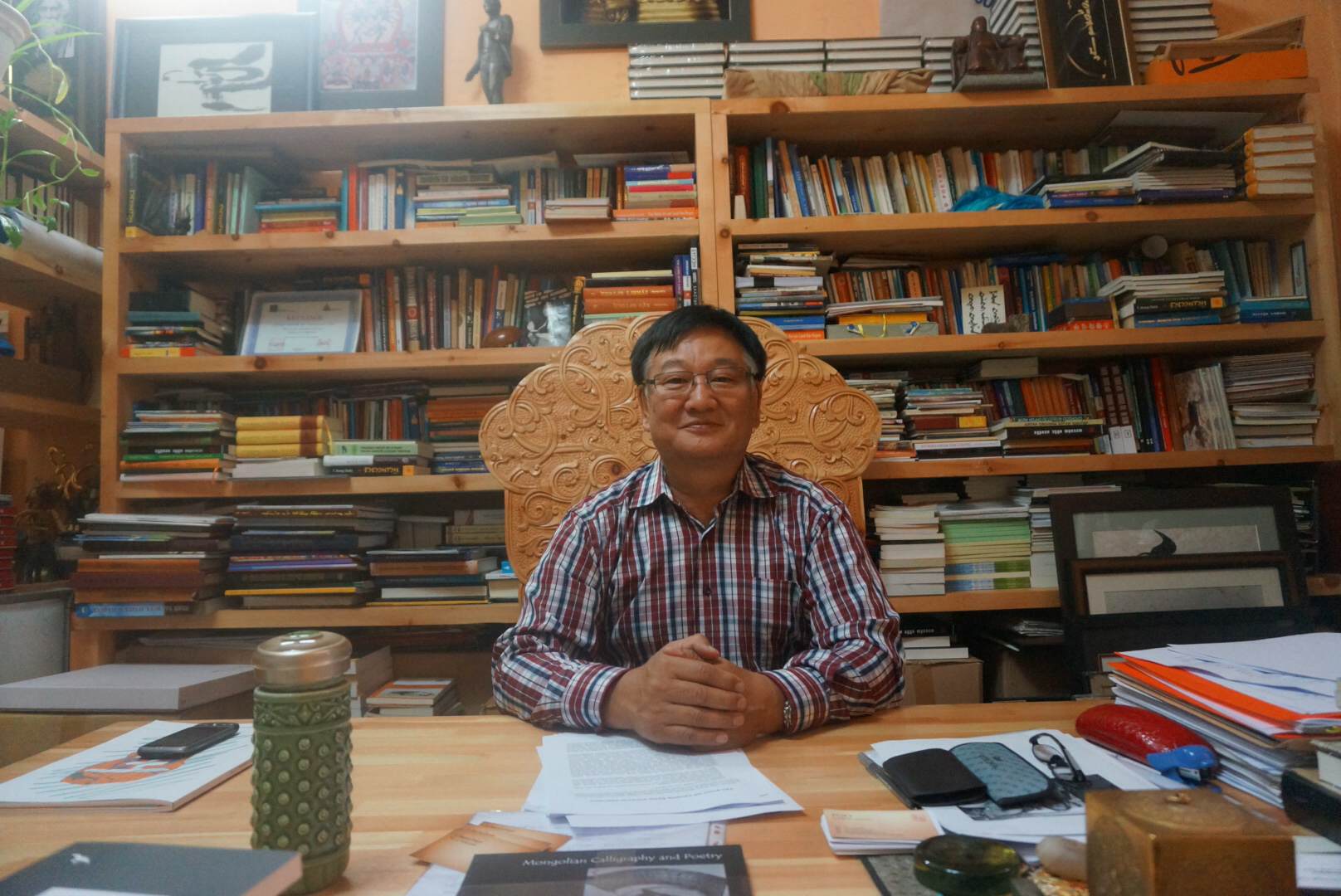

Led by his assistant Munkhnaran, we eagerly tip-toed into the studio of Mend-Ooyo. We were incredibly lucky to earn this opportunity we knew, introduced to him by our friend Gabby’s mother Elaine, who’d met him while working for the New York Times. Hearing high praise from Mongolian friends we’d made in Ulaanbaatar, we knew we were about to enjoy an encounter with one of the nation’s premiere intellectual minds. His studio was modest in size, but rich in literature and art. The walls were consumed by books, mostly Mongolian texts, but intermittent by international work. Where there was blank wall space hung fantastic pieces of calligraphy and traditional art.

Upon our arrival, Mend-Ooyo gladly stood up from the busy drafts of text collected atop his charming wooden desk to greet us with a smile and a handshake. He quickly gestured at us to take a seat with him at the table set up next to the door, where a display of crackers and drinks awaited. From this setting we began our conversation, Munkhnaran serving as our translator, and what we learned over the next 90 minutes provided an exceptional contextual capstone to our journey across Mongolia.

Mend-Ooyo is a nationally renowned poet, author, professor, and calligrapher. His role in Mongolian culture and society is one of great significance: through his publications, Mend-Ooyo intends to preserve and celebrate the unique traditions of the nomadic countryside. Our time together began with a sneak peak at a catalog which was set for release on September 18th that details the ancient art of an ethnic group from the eastern steppe. It is this type of narrowed focus on the oft forgotten Mongolian ethnic groups that exemplifies Mend-Ooyo’s dedication to his homeland. When asked about life on the countryside, he nostalgically recounted his experiences as a child on the eastern steppe. He insisted there was no need for his family to lock their yurt, even when away for several days. In fact, a passing traveler or herder would be encouraged to enter the yurt and help himself to a cup of tea. His father would take solace in seeing a used cup upon his return home, knowing his accommodations were useful to someone while he was gone. This help thy neighbor mindset was intrinsic across countryside communities. For example, Mend-Ooyo explained, if a herder were to find a stranded horse, he would take it upon himself to return it to its original herd, without mentioning it to the horse’s owner and without any expectation of appreciation, simply out of the kindness of his heart and the camaraderie he felt for his fellow herder. Life on the Mongolian steppe was not easy, but it was a major point of pride. There was no need for a general store, everything one needed ought to derive from the animals within the family’s domain. Summers were hot and winters were cold; he chuckled as he recalled riding between the humps of his camel, wrapped up warmly in animal wool, safely secured from the air’s brisk chill, besides exposure to his iced cheeks, turning a rosy red from the winter’s wrath.

Mend-Ooyo insisted that this romantic image of the Mongolian nomad is disappearing, as the socio-cultural gap between urban and rural Mongolia continues to close. Technology is sweeping the country, even deep into the remote countryside. On our 8-day trip across Mongolia, we encountered people with Galaxy smart phones and iPhones who lived on yurts, hundreds of miles from the nearest city. Mend-Ooyo fears that this newfound discovery of and reliance on technology is contributing to the deterioration of traditional Mongolian culture. He proudly asserts that he has no useless or unnecessary information trapped in his working memory, while the new generation struggles to keep track of things as simple as a phone number; this skill may have been something acquired from his early life back on the steppe.

After traveling through the large majority of ex-Soviet lands across Central Asia, a burning question for us became: How did Soviet influence over three-quarters of a century affect traditional Mongolia, especially education? When asked that question, the warm smile that glowed upon Mend-Ooyo’s face retreated, replaced by a serious and somber expression, accompanied by a sharp tone. In order to provide some insight into how Soviet customs warped Mongolian education, he told us a fascinating anecdote from his schooling back on the steppe. His soviet-educated teacher taught his class the names of all the colors of the rainbow, by their Soviet names. Mend-Ooyo cracked a grin, remembering that they already had names for hundreds of colors- red is not just “red,” there are dozens of variations that they have to learn and utilize in everyday life to describe the colors of the horizon or the landscapes they would travel around in order to properly assess meteorological forecasts or the type of land they were to cross.

In his poem “Wheel of Time,” he writes,

Roots of grass suck in the rain, grow saturates.

A flock of birds threads through the clouds,

And hills and mountains pass through a vision of horses,

And angry breath is obstinate.

A thread of golden sunlight pierces the flowers on the southern slopes.

Inconsistent as time is, the time flies by and is gone.

The time goes flying, flying by,

The time is gone, is gone.

We tried to relay to Mend-Ooyo that the countryside he so beautifully described to us still exists today, at least from what we witnessed in our weeklong tour de Mongolia. When we were seriously lost somewhere between Hovd and Altai, it was a young boy on a horse, no older than six, herding a massive throng of hundreds of sheep and goats, who directed us to the only bridge that would take us over a river blocking our passage to the next city. Mend-Ooyo nodded, as if to show that this was an occurrence to expect on the steppe. There, he explained, children are expected to contribute to the family at a much younger age. To us, this seemed to be part of why those on the steppe might be more willing, excited even, to adopt Western or urban conveniences.

It was hard for us to completely understand the extent to which Mend-Ooyo believes tourism has a positive influence on his country. On the one hand, he seemed particularly glad when we insisted we’d return to New York and laud the wonders and spectacles of exploring the Mongolian countryside with the help of our endless hours of footage, maybe even encourage friends and family to make the trip themselves. On the other hand, he dismissed the influence tourism has on Mongolian life, noting off hand that its ‘better than mining!’ At a deeper level, Mend-Ooyo didn’t seem particularly keen on tourism in the same way those of us in the West view it. He’d prefer tourism exist in the most natural way possible – people should see Mongolia for what it is naturally, not some distorted inauthentic representation of it. He loved that we pulled to the side of the road and eagerly asked to help a family build their yurt for the new season. Conversely, the idea of creating brand new mini tourist establishments to encourage foreign visitors was as detrimental to the country as it was to the foreigners distorted image of Mongolia. We saw the beginnings of this tourism industry ourselves, as we drove towards Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital. There was an entire town, billboards on the highway included, with “camel rides” available and yurts atop restaurants to get a “taste” of real Mongolia. We were just as happy to stop on the rocky roads in the middle of nowhere to ask polite nomads at their humble yurts for directions. Oftentimes they’d kindly invite us inside for a cup of tea and maybe even some mare’s milk (distilled alcohol) if we were lucky. We’re sure Mend-Ooyo would agree, this is the true Mongolian experience.

To learn more about Mend-Ooyo, please visit his website at http://www.mend-ooyo.mn/index.php?langid=2

Hey you! Thanks for reading.

Want to join our weekly mailing list for more great updates from us?